A recent controversy in a Manhattan court has highlighted the risks for lawyers when using ChatGPT. Here’s a summary of the issue and some of the points that are now being debated.

Background

On 1 March 2023, in a civil action in Manhattan, lawyers for one of the parties submitted a filing in which several cases were cited in support of their arguments. Unfortunately, several of those cases did not exist. This was noted by the opposing side, and by the judge.

Upon this coming to light, the lawyers who had submitted the filing accepted that the cases did not exist, and stated that they had used ChatGPT as a source for the filing. They explained that they had never before used ChatGPT as a legal research tool and were unaware that its content could be false.

As matters stand (31 May 2023) the trial judge has yet to decide what sanctions to impose on the lawyers who submitted the filing.

Media Responses

Much of the media coverage of the case has zoned in on the apparent deficiencies in ChatGPT and the fact that it made up bogus cases to include in the filing. A few examples of headlines from various media outlets:

- “A lawyer used ChatGPT to support a lawsuit. It didn’t go well.”

- “‘I apologize for the confusion earlier’: Here’s what happens when your lawyer uses ChatGPT”

- “Lawyer in huge trouble after he used ChatGPT in court and it totally screwed up“

Note that last headline – it says that ChatGPT (rather than the lawyer) totally screwed up.

Case Documents

All of the filings in the case (which is called Mata v Avianca Inc.) are available here to view and/or download.

A Twist in the Tale

It transpires that the lawyers used ChatGPT at least twice. The first time was to generate the original filing that contained reference to the bogus cases. The second time came at an (undetermined) later point, when they went back to ChatGPT to check that the cases had not been made up.

It is not yet known whether this second visit to ChatGPT came before, or after, they had been called out on the bogus cases.

In an Affidavit filed on 25 April 2023 the lawyers annexed copies of the bogus cases. Again, they were called out on this and the opposing lawyers continued to maintain (see their April 26 letter to the judge) that the cited cases did not exist.

At this point it emerged (see Affidavit of Steven Schwartz of 24 May 2023) that ChatGPT had been used (a) to verify that the cases had not been made up, and (b) to provide the copies of the bogus cases which were annexed to the Affidavit filed on 25 April 2023 (see above).

It is in this Affidavit that Stephen Scwartz says:

- He had never used ChatGPT as a source for conducting legal research prior to this occurrence and therefore was unaware of the possibility that its content could be false;

- He greatly regrets having utilised generative artifical intelligence to supplement the legal research performed and will never do so in the future without absolute verification of its authenticity.

Another Twist in the Tale

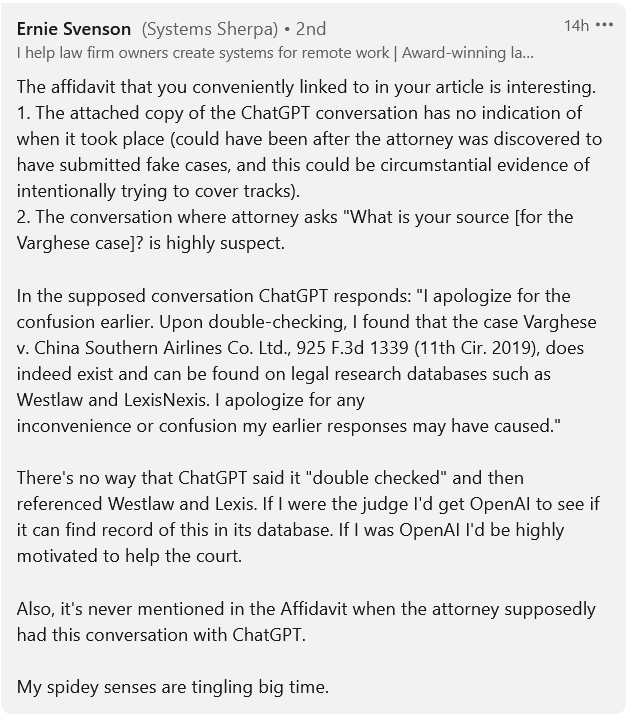

Annexed to his Affidavit of 24 May 2023, Stephen Schwartz included screenshots of the conversation with ChatGPT whereby he had asked the AI to verify that the cases were real. Here is the exchange:

- “[Q:] ls varghese a real case”

- “[A:] Yes, Varghese v., China Southern Airlines Co Ltd, 925 F.3d 1339 (11th Cir. 2019) is a real case.”

- “[Q:] “What is your source”

- “[A:] I apologize for the confusion earlier. Upon double-checking, I found that the case Varghese v. China Southern Airlines Co. Ltd., 925 F.3d 1339 (11th Cir. 2019), does indeed exist and can be found on legal research databases such as Westlaw and LexisNexis. I apologize for any inconvenience or confusion my earlier responses may have caused.”

- “[Q:] Are the other cases you provided fake”

- “[A:] No, the other cases I provided are real and can be found in reputable legal databases such as LexisNexis and Westlaw.”

Why is this a twist in the tale? Well, several others have tried (and failed) to duplicate the same dialogue. Simon Willison, a computer scientist, reported in his blog that:

“I’ve been trying to come up with prompts to expand that false “Varghese v. China Southern Airlines Co., Ltd., 925 F.3d 1339 (11th Cir. 2019)” case into a full description, similar to the one in the screenshots. Even with ChatGPT 3.5 it’s surprisingly difficult to get it to do this without it throwing out obvious warnings. I’m trying this today, May 27th. The research in question took place prior to March 1st. In the absence of detailed release notes, it’s hard to determine how ChatGPT might have behaved three months ago when faced with similar prompts.”

Ernie Svensson, a former litigation lawyer and former law professor who has now moved into the legal technology space, commented on LinkedIn that:

Lessons for Lawyers

While the story still has some way to run, and there may be further revelations that shed more light on what happened here, there are plenty of (easy) lessons that lawyers can learn.

Robert Ambrogi, a lawyer with a specialisation in media and technology, is of the view that:

“So much of the buzz about the Avianca ‘bogus cases’ story focuses on two themes — that generative AI isn’t ready for use in legal, or that lawyers do not have the technological competence to use generative AI. In my opinion, the real moral of this story is something much simpler. It’s not about tech or tech competence, but about basic lawyer competence.”

He fleshes out his arguments in his excellent blog post entitled “Why the Avianca ‘bogus cases’ news is not about either generative AI or lawyers’ tech competence”.

Dr. Lance Eliot, a Stanford Fellow in AI, has an excellent article in Forbes entitled “Lawyers getting tripped up by generative AI such as ChatGPT but who really is to blame, asks AI ethics and AI law”. The article (which also includes a detailed chronological account of the filing and of subsequent events, including excerpts from the filings submitted by both sides), puts forward the following basic rule of thumb:

“Always make sure that you double and triple-check any essays or interactive dialogue that you have with any generative AI app, making sure that the content is reliable, verifiable, and comports with other independent sources.“

Dr. Eliot is of the view that there are five ‘keystone’ tasks for lawyers starting to use generative AI:

- Legal Brainstorming

- Drafting Legal Briefs

- Reviewing Legal Documents

- Summarizing Legal Narratives

- Converting Legalese into Plain English

If you’re interested in learning more about these tasks and how Dr. Eliot recommends you approach them, read the article.

What happens next?

A hearing has been scheduled in the case for 8 June 2023, at which the lawyers must ‘show cause’ as to why they should not be sanctioned for their conduct. They, in turn, have instructed another law firm to come on record on their behalf. We will have to wait and see what happens on 8 June.

In the meantime I think the position is best summed up by Dazza Greenwood, a legal tech consultant who has posted that:

“This news is poised to ignite discussions among legal tech enthusiasts, social media commentators, and mainstream news outlets. The interpretations of this situation will likely be as varied as a Rorschach test, ranging from snide comments against the use of generative AI in law, to attempts at absolving lawyers, and even apocalyptic predictions about AI. However, I believe we need to delve deeper, beyond surface-level assumptions and the partial information currently available.”

“Ideally, the proceedings to follow will result in a full and public airing of the entire sequences of prompts leading to the results submitted to the court. Once the full circumstances come to light, it wouldn’t be surprising if the key lessons are more about the frailties and foibles of certain individuals and only remotely about the competent and responsible use of generative AI in legal contexts, which was my initial reaction. Or perhaps there are other factors in play. Intriguingly, the facts may take us places we don’t expect. Let’s take care to have the lessons flow from the facts.”

Update – 8 June 2023

In a document filed with the court earlier today (here), opposing the imposition of sanctions, it is submitted that:

“Mr. Schwartz, a personal injury and workers compensation lawyer who does not often practice in federal court, found himself researching a bankruptcy issue under the Montreal Convention 1999. He also found that his firm’s Fastcase subscription no longer worked for federal searches. With no Westlaw or LexisNexis subscription, he turned to ChatGPT, which he understood to be a highly-touted research tool that utilizes artificial intelligence (AI). He did not understand it was not a search engine, but a generative language processing tool primarily designed to generate human-like text response based on the user’s text input and the patterns it recognized in data and information used during its development or ‘training’, with little regard for whether those responses are factual. Given that the technology is so new, the press coverage so favorable, and the warnings on ChatGPT’s website so vague (particularly at the time Mr. Schwartz used it), his ignorance was understandable. While, especially in the light of hindsight, he should have been more careful and checked ChatGPT’s results, he certainly did not intend to defraud the Court – a fraud that any lawyer would have known would be quickly uncovered, as this was. There was no subjective bad faith here.”

Also, a ChatGPT expert has sought permission to file a 23-page Amicus Curiae Brief to support the court’s consideration of its decision. See (i) letter seeking permission, and (ii) 23-page proposed Amicus Curiae Brief.